Job Orchestrator End-to-End Design Journey

Introduction

Spark has become the engine of the modern data platform — fast, scalable, and proven.

But engines need more than horsepower; they need control systems. Without the right orchestration, even the best engine stalls.

At IOMETE, we faced exactly this challenge. Spark jobs had grown in number and complexity, but our orchestration system couldn’t keep up. Business-critical jobs were delayed by trivial ones, deadlocks left jobs hanging indefinitely, and users had little visibility into what was really happening behind the scenes.

So we set out to build what was missing: a true Job Orchestrator that could bring order to Spark workloads.

Existing System

Our starting point was the Spark Operator on Kubernetes. This operator enabled us to define Spark jobs as YAML resources, allowing Kubernetes to handle the rest.

The process looked simple:

- User created a Spark job request via the IOMETE console.

- Backend generated the YAML spec and pushed it to Kubernetes.

- The Spark Operator picked it up and executed it.

While this worked for smaller workloads, it broke down at scale:

- No prioritization: All jobs went into the same pool. A low-value job could block a high-priority one.

- Deadlocks: Drivers started, but executors couldn’t find resources → job stuck forever.

- Over-provisioning: Users requested more CPU and memory than needed, hogging cluster resources.

- Low visibility: Only the latest 1,000 jobs were visible, with no historical context or time-series tracking.

The Spark Operator was a great executor, but it wasn’t a true orchestrator.

Our Design Goals

To fix this, we laid down a few simple but critical goals:

- Smarter queuing: High vs normal priority queues, with clear fairness rules.

- Namespace isolation: Each namespace has its own queues, avoiding noisy neighbor effects.

- Capacity-aware job submission: Don’t launch jobs if the cluster doesn’t have room to run them.

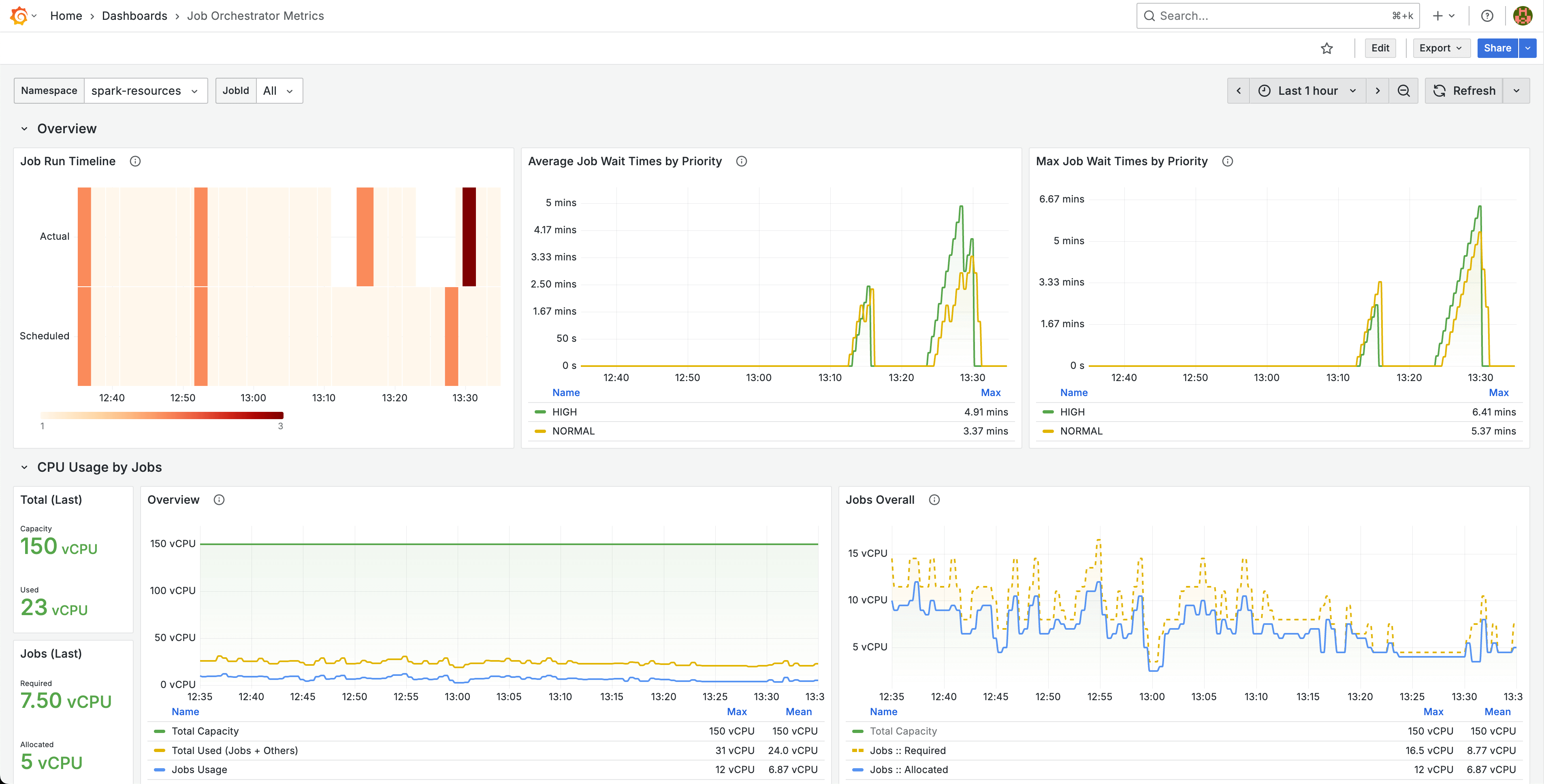

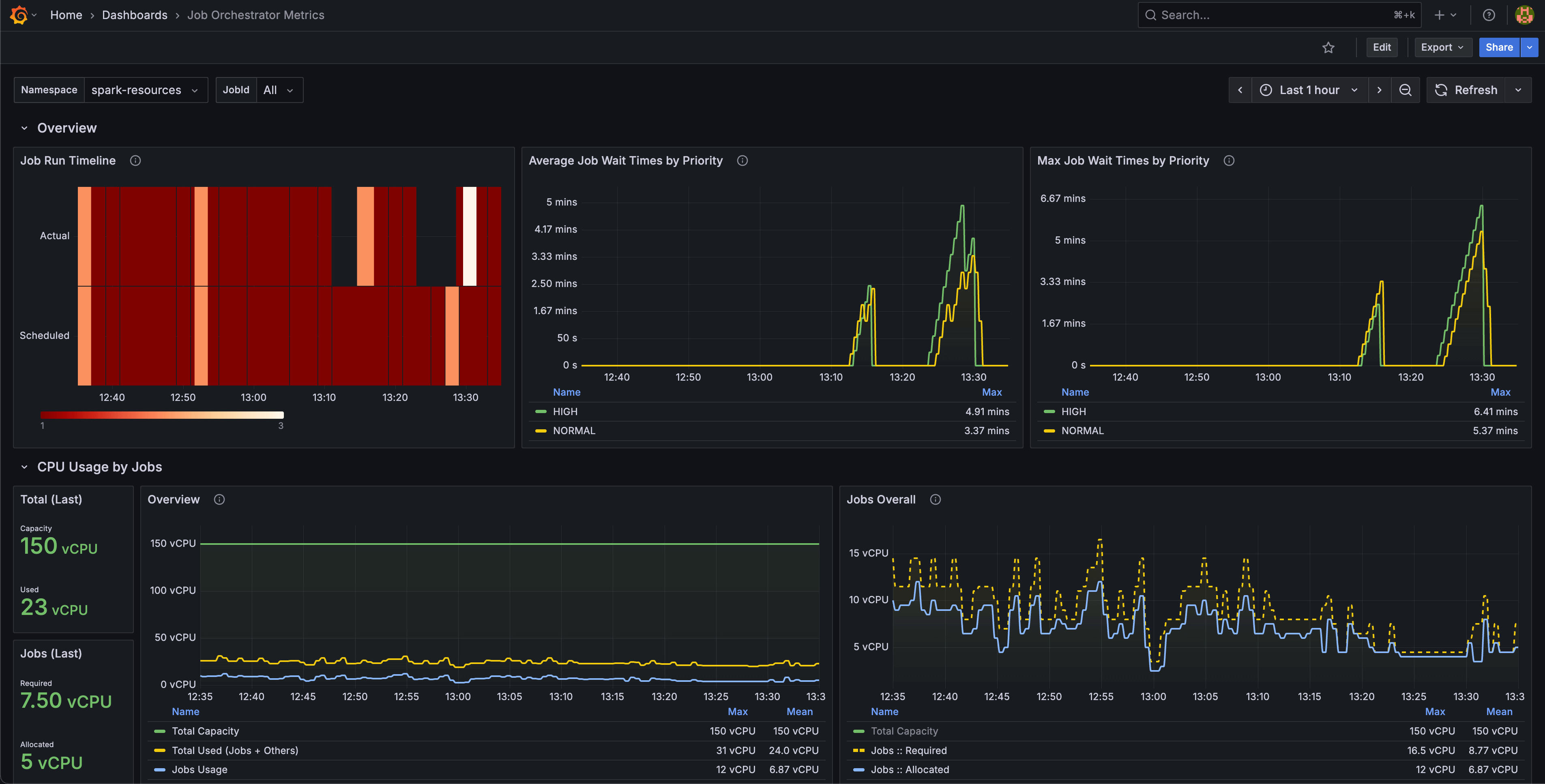

- Visibility & monitoring: Real dashboards for job metrics, queue wait times, and cluster utilization.

New System Components

We broke the solution into distinct components:

1. Queues & Scheduler

We introduced two levels of queues:

- High Priority — for business-critical jobs.

- Normal Priority — default for all others.

Inside each level, jobs are processed FIFO (first-in, first-out).

Each namespace gets its own isolated queues, so workloads from one team can’t overwhelm others.

2. Submitter & The Capacity Checker

The submitter is the engine that continuously polls queues and decides which job to run next. But before it launches anything, it calls in the Capacity Checker — a safeguard that ensures we don’t submit jobs the cluster can’t handle.

3. Metrics Plane

We knew from experience that visibility matters as much as scheduling. The orchestrator continuously collects metrics like:

- Queue lengths

- Average queue wait times

- Job schedule/run counts

On top of that, we wanted dashboards to track:

- Real-time vs historical cluster usage

- Resource consumption by job & namespace

- Patterns in queue wait times and job bottlenecks

Architecture and Design Choices

Capacity Checker

The capacity checker became one of the most critical parts of our new design. Without it, we risked falling back into the same trap as before: jobs entering the cluster, drivers starting, but executors never finding space, leaving jobs in a failed or stuck state.

The question we had to answer was:

“How do we know the cluster has enough capacity before submitting a job?”

We explored multiple approaches:

1. Kubernetes API-based checks

This was the simplest solution: query Kubernetes directly to calculate available CPU and memory. If the cluster had enough for the driver + executors, the job could be submitted.

It was easy to implement, with no extra moving parts, and it worked with existing Kubernetes client libraries.

✅ Gave us a quick and lightweight way to prevent obviously impossible jobs from entering the cluster.

⚠️ It’s only a snapshot in time. Resources could disappear between the check and the actual submission — leading to occasional race conditions.

This trade-off was acceptable for an MVP: solve 80% of the problem quickly, then iterate.

2. Dry-run submissions

Instead of asking Kubernetes for resources, what if we asked Kubernetes to simulate scheduling the job? By using the dryRun=All API, we could effectively ask the scheduler:

“Would this job fit right now?”

Unlike raw API checks, this respects Kubernetes scheduling constraints like taints, affinities, and topology.

✅ Much more accurate, we get the scheduler’s actual answer.

⚠️ It’s slower, adds latency, and error handling gets tricky. The dry-run API returns verbose errors that we’d need to parse carefully to tell whether it failed due to resources or invalid specs.

We liked the accuracy, but the extra complexity made us park this as a future option.

3. Placeholder pods

A clever but heavier idea is to create lightweight pods (similar to YuniKorn) that request the same resources as the Spark job (driver + executors). If these placeholders got scheduled, we knew the real job would too. Once confirmed, delete the placeholders and launch the actual Spark job.

Placeholder pods don’t just check resources; they actually reserve them, mitigating most race conditions.

✅ High confidence, if placeholders run, the real job almost certainly will.

⚠️ Adds a lot of cluster churn. Placeholders temporarily consume resources without doing work. We’d also need solid cleanup logic to avoid orphaned pods.

This felt too heavy for our first iteration, but it remains an attractive long-term option for bulletproof scheduling.

Final MVP Choice

We decided on Kubernetes API-based checks as our first step. It gave us:

- A fast, low-friction implementation.

- Enough reliability to prevent the majority of deadlocks.

- A baseline we can evolve toward dry-runs or placeholders later.

Job Orchestrator

Parallel to designing the capacity checker, we also had to decide:

“What system will orchestrate our jobs end-to-end?”

We compared four main options:

1. Spark Operator

The most lightweight option was to stick with Spark Operator and build queuing logic around it.

✅ Battle-tested, reliable for Spark jobs and already part of our stack.

⚠️ Limited to Spark only. No queueing, prioritization, or orchestration features. We’d have to build everything (queues, retries, metrics) ourselves.

We ruled this out as the operator is a great executor, but not an orchestrator.

2. Kubernetes Volcano

We considered going all-in on Volcano, a batch scheduler built for AI/ML and Spark workloads.

✅ Has priority queues, gang scheduling, and preemption support. Very robust for fair scheduling in shared clusters.

⚠️ Doesn’t handle time-based scheduling (cron-like jobs). Lacks job history and user-facing dashboards. More of a low-level scheduler than a full orchestrator.

Volcano was tempting for raw scheduling, but it didn’t give us orchestration, monitoring, or retries.

3. Prefect

A Python-based orchestration system (Prefect) that was quick to set up and came with a lot of orchestration features out of the box.

✅ Provides DAG orchestration, retries, scheduling, and manual runs, as well as native integrations with DBT and Python jobs.

⚠️ Not a true priority-queue system. Each priority level requires a separate queue. No native DLQ, so failures need manual handling.

Despite trade-offs, Prefect was a great MVP choice as it solved 70% of our problems with minimal setup.

4. Custom Setup

A DIY path was to use message queues (like RabbitMQ, etc) for priority queues and DLQs, build a custom submitter, and wire everything to Spark Operator.

✅ It gave us fine-grained control with strict priorities, DLQs, TTLs, purge, and requeueing. And could also support all job types (Spark, SQL, DBT, Python).

⚠️ High upfront engineering cost. Requires maintaining multiple new components (cron, queues, submitter logic, monitoring).

This was the most flexible but also the heaviest lift, not right for MVP.

Final Choice

We chose Prefect for the MVP. It gave us orchestration, retries, and observability without a huge investment.

The philosophy was simple: don’t reinvent the wheel where we don’t have to.

Final Design

The final Job Orchestrator design combines:

- Priority queues (High, Normal, namespace-isolated).

- Submitter with Capacity Checker (API-based for MVP).

- Prefect for scheduling & orchestration.

- Prometheus metrics & Grafana dashboards for real-time + historical monitoring.

This design gave us:

- Predictable job scheduling.

- Better cluster utilization.

- Transparency for engineers debugging stuck jobs.

- A flexible foundation for supporting future workloads.

Conclusion

We started with simple solutions (API-based capacity checks, Prefect for orchestration) and avoided over-engineering. The result is a system that not only works today, but also leaves room for future growth — DLQs, preemption, multi-job support, and cost intelligence.

👉 Want to dive deeper on Spark Jobs in IOMETE: Spark Jobs Guide