Data Lakehouse Encryption: Encrypting Data at Rest in Apache Iceberg

Modern data lakehouses built on Apache Iceberg often store petabytes of sensitive data across shared object stores like S3, making encryption at rest non-negotiable for compliance (HIPAA, GDPR) and data sovereignty.

Encryption in transit (via TLS) protects data moving between services, while at-rest encryption safeguards files on disk against theft, insider access, or breached storage credentials.

Here at IOMETE, we help customers run data lakehouses ranging from hundreds of gigabytes to multiple petabytes. These environments often contain highly strategic information, as well as data protected under HIPAA, GDPR, and other regulatory frameworks. In this article, we explore how to protect that data using encryption for data stored in Apache Iceberg tables on modern object stores such as S3.

Why Encrypt Data at Rest in a Data Lakehouse?

A common security mistake is to assume that as long as bad actors cannot access your application, they also cannot access the data it stores. In reality, data can be compromised in many other ways. Encryption at rest protects sensitive data when someone gains access to your network, your servers, or the physical disks themselves, without ever accessing the application.

To make this more concrete, imagine a heist where someone breaks into a data center operated by a major cloud provider and steals a large number of hard disks. If the data on those disks is not encrypted, the thieves can immediately start mining it for valuable and sensitive information. If the data is properly encrypted, breaking that encryption would require significant time and resources. Without even knowing what data is stored on the disks, which could just be all cute cat pictures, most thieves will not attempt it in the first place.

Security algorithms have always relied on the sender and receiver sharing a way to encode and decode a message. One of the oldest and simplest examples, dating back to Roman times, is an offset in the Latin alphabet. To encrypt a message, each letter is replaced with another letter a fixed number of positions away, also known as the Caesar cipher. For example, using an offset of 5, the sentence “This is an encrypted message” becomes “Ymnx nx fs jshwduyji rjxxflj” and is unreadable.

The Caesar cipher, of course, is relatively easy to break by trying different combinations. Over time, this basic idea evolved into much more complex systems. During World War II, the Germans used the Enigma machine, which applied a far more sophisticated version of this concept. Its encryption was eventually broken by a team led by Alan Turing, regarded as one of the fathers of modern computing. To do so, his team built early computing machines, creating one of the first examples of using a machine to break encryption produced by another machine.

Envelope Encryption and Key Rotation

Modern encryption at rest typically uses well-established algorithms such as AES-256. These algorithms are extremely strong, but a shared secret key is still needed to both encrypt and decrypt the data. If that key is ever leaked, all data encrypted with it is at risk if bad actors gain access.

Since it can be difficult to know whether a key has ever been leaked, a best practice is to rotate keys regularly. Many organizations rotate keys every 90 days, or even more frequently, depending on regulatory or security requirements.

This naturally raises a concern: if you have terabytes of data, do you need to re-encrypt everything each time a key is rotated? Re-encrypting that amount of data would be extremely time-consuming and expensive. Fortunately, modern systems use a technique called envelope encryption to solve this problem.

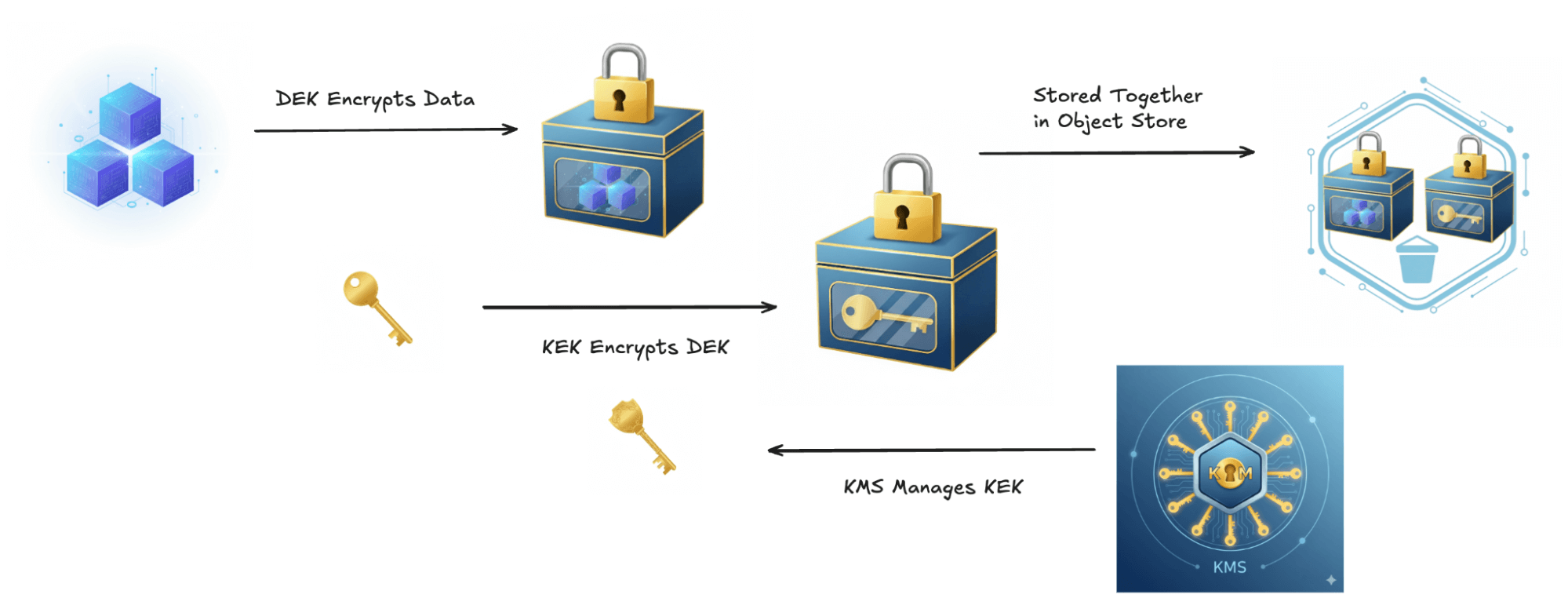

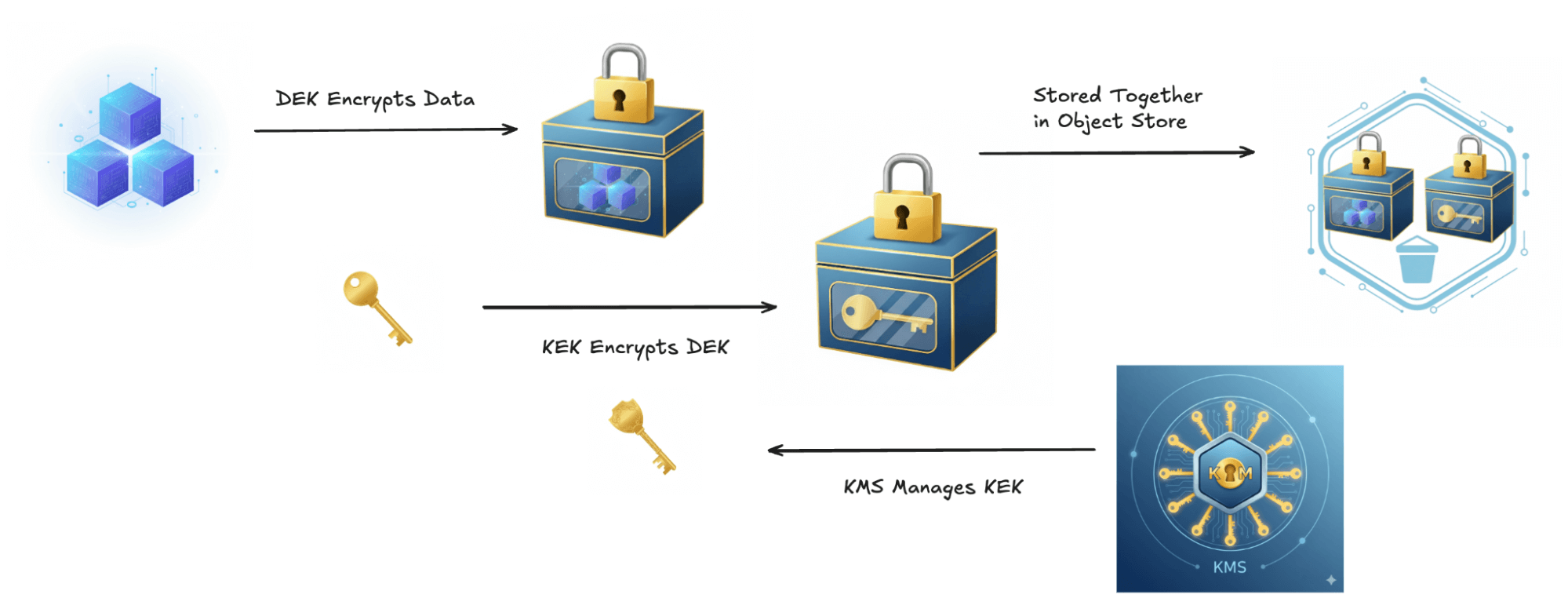

Envelope encryption uses two different keys: a Data Encryption Key (DEK) and a Key Encryption Key (KEK). The DEK works as you would expect: the encryption algorithm takes your data and the DEK as input and produces encrypted data as output.

Since the DEK itself is just data, it can also be encrypted. The KEK is used to encrypt the DEK. The encrypted DEK is then stored as metadata alongside the data encrypted with that DEK. When it comes time to rotate keys, only the KEK is rotated. This means you only need to re-encrypt the DEK for each object, rather than re-encrypting the underlying data itself.

Managing Encryption Keys

Now that we have established how encryption keys are used, the next question is how those keys are created, stored, and rotated safely. Today, this responsibility is typically handled by a dedicated Key Management System (KMS).

Modern KMS implementations maintain multiple versions of each key. When a key is rotated, a new version is created, while older versions remain available to decrypt data that was encrypted in the past. Having multiple key versions also enables gradual re-encryption strategies. Instead of re-encrypting all data at once, which would be a logistical nightmare at scale, systems can re-encrypt data incrementally over time as objects are accessed or rewritten.

Under the hood, encryption keys in a KMS are often stored in Hardware Security Modules (HSMs). These tamper-resistant hardware devices are designed to securely manage cryptographic keys. Even if the hardware is stolen, extracting the keys is extremely difficult. You may already have similar hardware in your smartphone, as Apple, Google, and Samsung use HSMs or secure elements to protect payment and wallet functionality.

Most cloud providers offer managed KMS services backed by HSMs, such as AWS KMS, Azure Key Vault, and Google Cloud KMS. For organizations running in multi-cloud, hybrid, or on-premises environments, systems like HashiCorp Vault are commonly used.

In large enterprises, access to the KMS is often deliberately separated from access to applications and data. A dedicated security or platform team manages the KMS, while application administrators never see the raw keys. Applications are granted limited, audited permissions to use specific keys rather than direct access. This separation of duties reduces the risk of insider threats and limits the blast radius if an individual system or account is ever compromised.

Encrypting Apache Iceberg Tables in Object Storage

There are two main approaches to encrypting data in object stores:

- Client-Side Encryption (CSE): The client encrypts the data before sending it to the object store, which then simply stores the encrypted data.

- Server-Side Encryption (SSE): The object store encrypts the data as it is written to disk. SSE has multiple sub-variants, which we explore below.

Even when the object store handles encryption, data is typically transmitted securely over the network using SSL/TLS to guarantee encryption in transit.

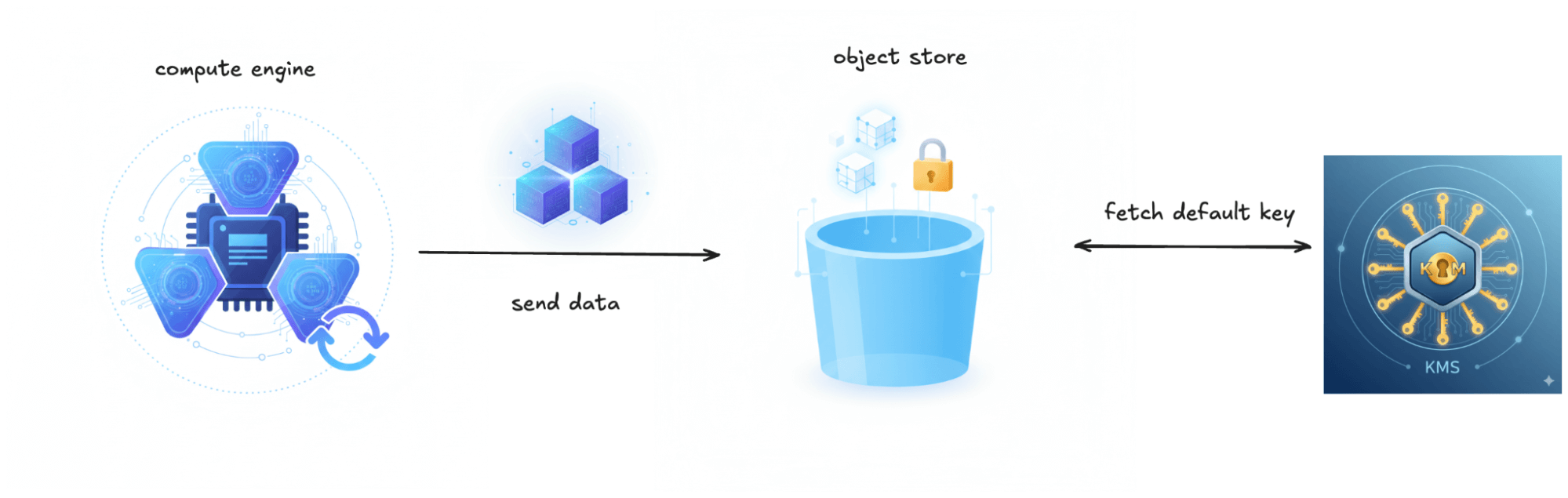

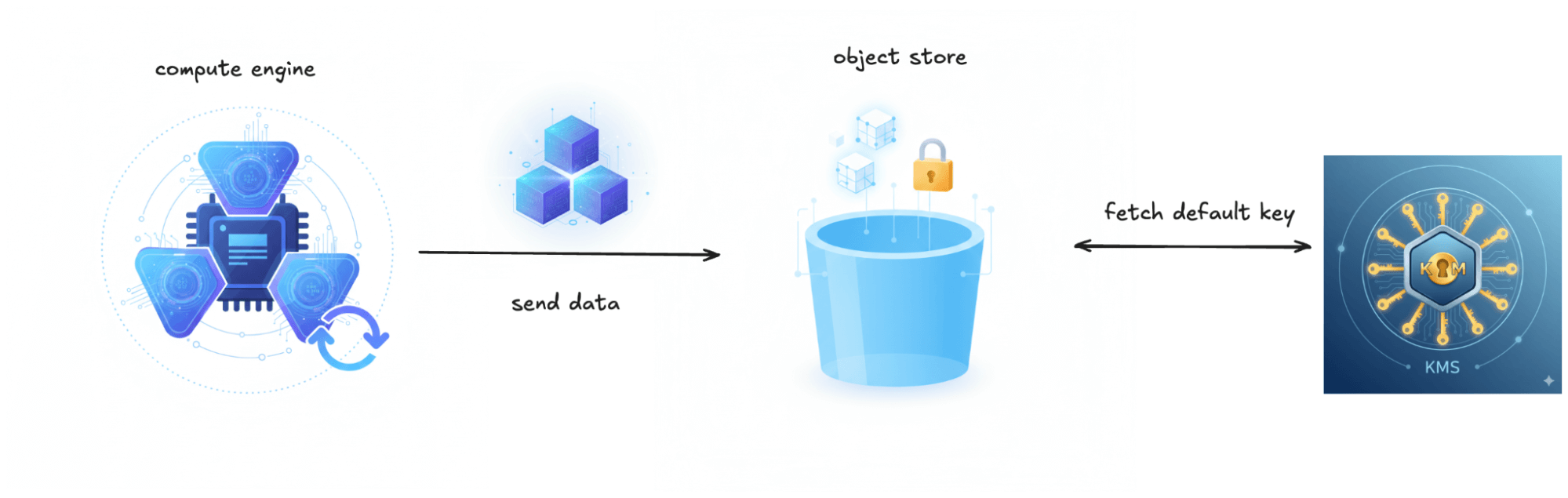

SSE: Platform-Managed Keys

This is the most common form of encryption used for object stores. AWS calls it SSE-S3, Google Cloud calls it Google-managed keys, and Azure calls it Microsoft-managed keys.

In this approach, the object store is connected directly to a KMS system. While each object is encrypted with its own unique DEK, the platform controls the master keys (KEKs) used to encrypt these DEKs. The same master key is typically used across your account, or sometimes at the bucket level. Key rotation is handled seamlessly by the object store and is transparent to clients. Performance impact is minimal.

For Iceberg tables, this means all your Parquet data files, manifest files, and metadata files are encrypted transparently. No special configuration is needed; you just write to an encrypted bucket and Iceberg works normally.

What it protects against: Physical disk theft, improper hardware disposal, or someone gaining access to the storage layer without proper credentials. Without access to the object storage service itself, encrypted data remains unreadable.

Advantages: Simple to enable with minimal operational overhead and suffices for most security needs. Meets encryption-at-rest requirements per most compliance frameworks.

Downsides: Limited visibility into which users trigger key operations. There is no granular control: you cannot revoke access to specific data by disabling keys, nor can you grant different encryption permissions to different users. If platform keys are ever compromised, the blast radius can be large.

Important to understand: Access control happens entirely at the object storage level. Anyone who can read an object through the storage service can access its contents, as the platform handles encryption and decryption transparently. Your encryption keys provide no additional access control beyond IAM policies.

When to use: General-purpose workloads where simplicity matters more than granular control. Perfect for development environments, internal analytics data, or any situation where your IAM policies already define your security boundaries.

SSE: Customer Specifies Keys

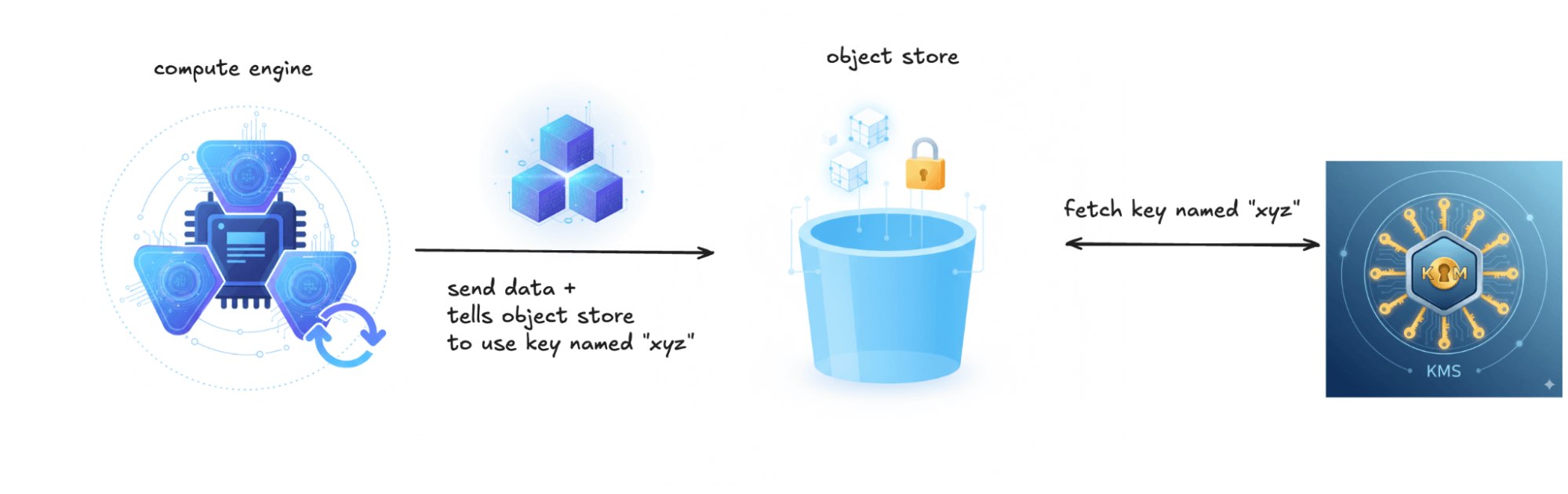

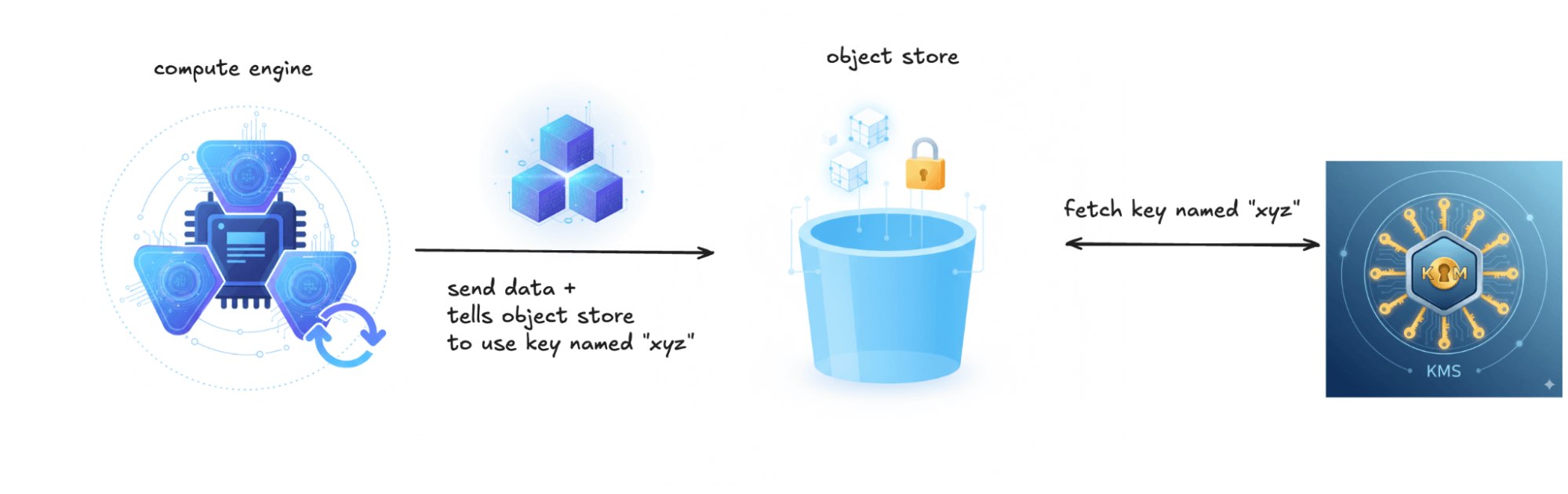

This approach gives you more granular control. The object store still handles the encryption mechanics, but you specify which KMS key to use. Each object still gets its own unique DEK, but now that DEK is encrypted with your specified KEK. This is known as SSE-KMS in AWS and customer-managed keys (CMEK) in GCP and Azure.

For Iceberg on S3-compatible storage, SSE-KMS is configured at the compute layer via Iceberg’s S3FileIO. Query engines such as Spark or Trino configure Iceberg’s S3 access with a specific SSE-KMS mode and KMS key, which is then applied when writing objects. At runtime, each engine instance or catalog is typically configured with a single active write key, meaning all newly written objects use that key. As a result, all objects that a given engine instance needs to read must be decryptable using that key. Managing multiple keys therefore requires careful separation of jobs, catalogs, or engine instances.

What it protects against: Everything that platform-managed keys protect, plus compromised IAM credentials (if the attacker lacks KMS permissions), overly broad storage permissions, and insider threats from users who have storage access but not key access.

Advantages: Different teams and applications can isolate their data using different keys within the same bucket. You get full audit logs showing exactly who accessed which keys and when. You can instantly revoke access by disabling a key, even if someone still has object permissions. If a key is compromised, the blast radius is limited to objects encrypted with that specific key.

Downsides: You must track which keys are assigned to which datasets or applications to avoid accidentally deleting or disabling a key still in use. Deleting a key that is still in use is catastrophic: lose the key and you brick the data. Storage and KMS permissions must both be correctly configured. KMS API calls can add up in high-volume workloads.

Important to understand: Access now requires both object permissions and key permissions. The storage service still handles encryption transparently, but it uses your identity to request key access from KMS. Even with storage credentials, data remains protected without key access.

When to use: Multi-tenant object stores where data from different customers is stored within the same bucket, or any scenario where highly sensitive data needs key-level isolation and auditability.

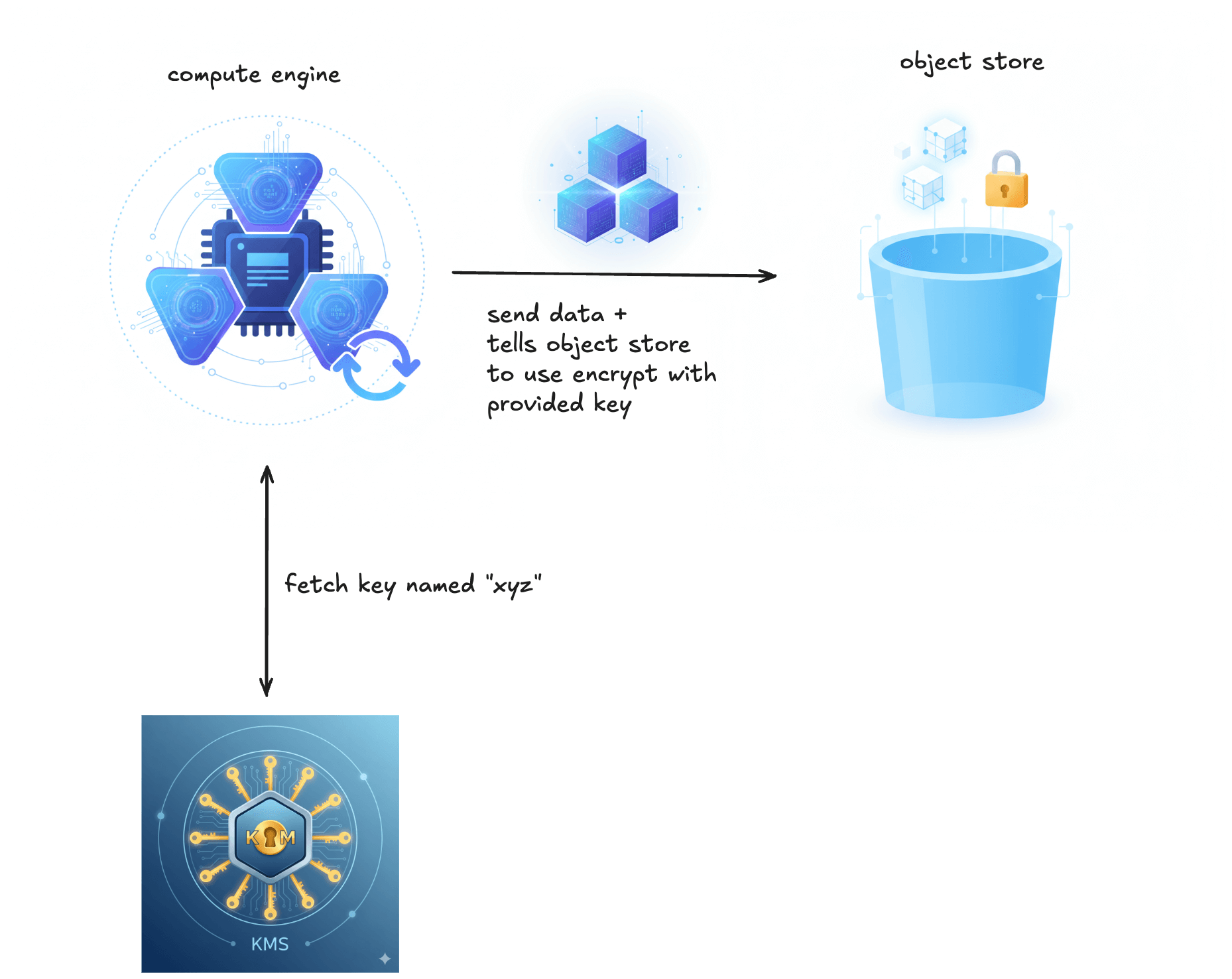

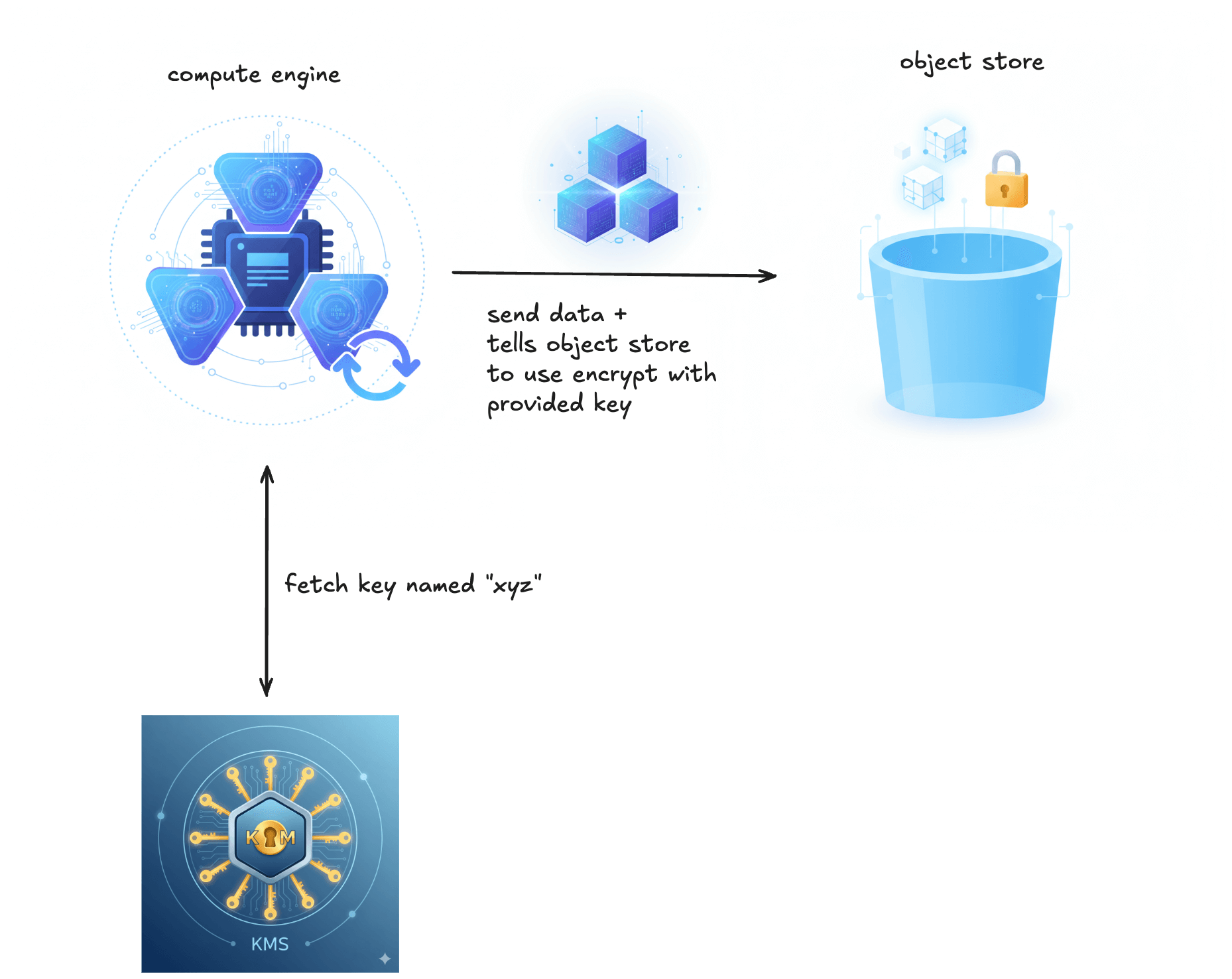

SSE: Customer Supplies Keys

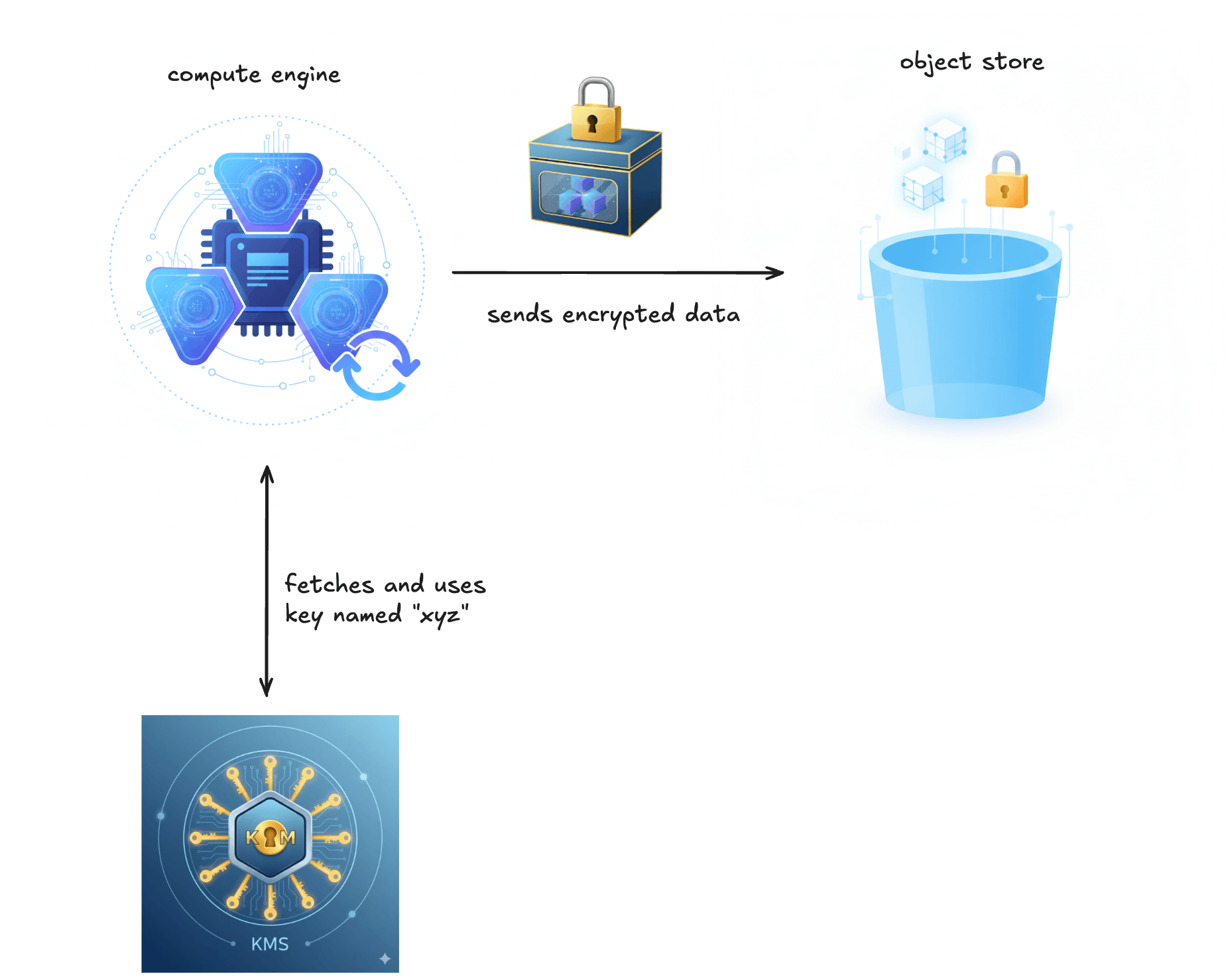

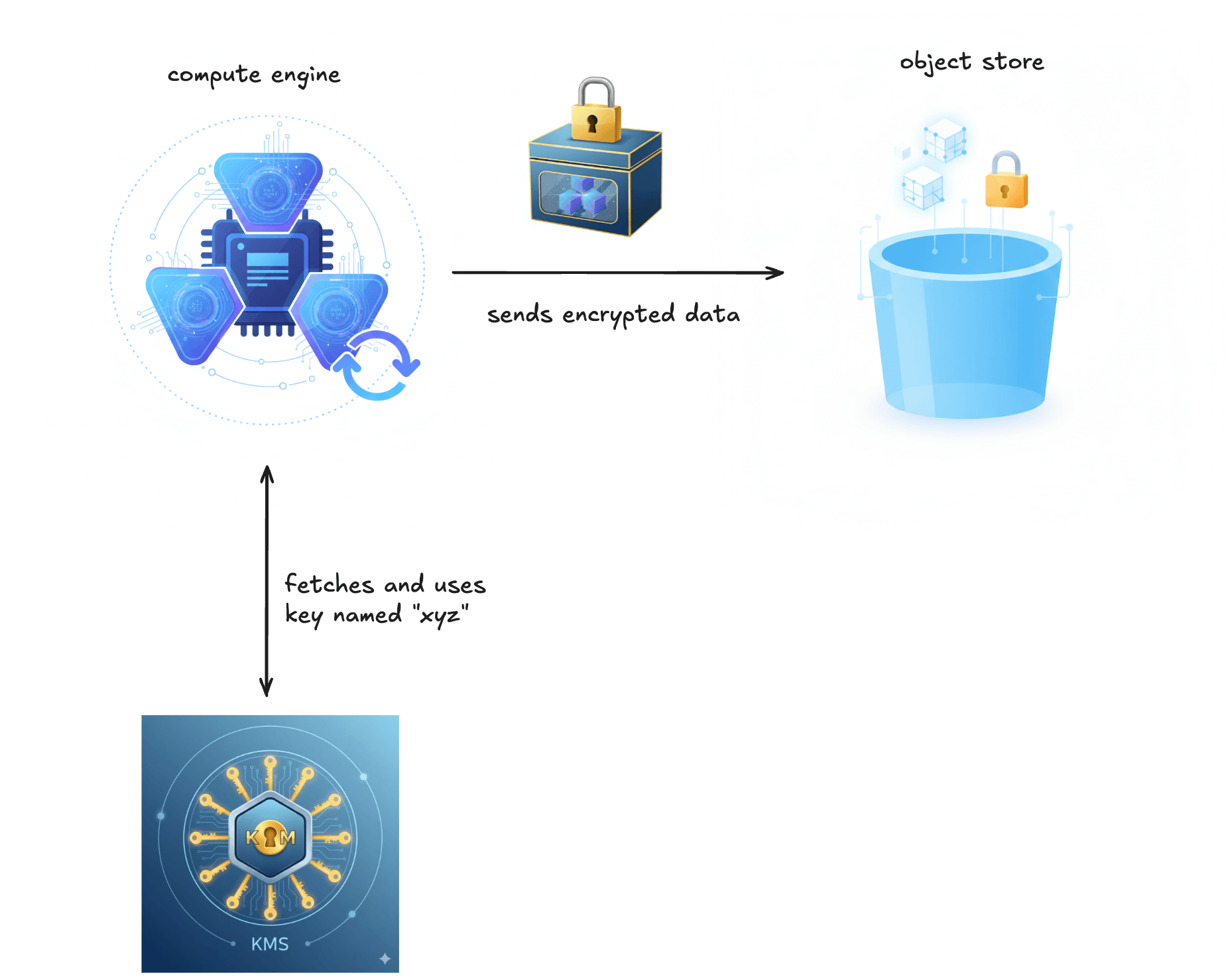

This is the most hands-on and operationally demanding form of server-side encryption. The storage system still performs encryption and decryption, but you must provide the encryption key with every request. The object store itself never connects to the KMS directly; applications and clients are responsible for retrieving the key and supplying it with every read and write. This is referred to as SSE-C in AWS S3, CSEK in GCP, and Customer Provided Keys in Azure.

For Iceberg on S3-compatible storage, SSE-C is also configured at the S3FileIO layer by selecting s3.sse.type = custom. Unlike SSE-KMS, the compute engine must be provided with the raw encryption key at startup. The engine does not retrieve keys from a KMS; it simply passes the supplied key to the object store on every read and write. This requires a secure mechanism to inject the correct key into each job or cluster at startup. All engine instances that need to access the data must be configured with the same key.

What it protects against: Everything that customer-specified keys protect against, plus scenarios where encryption key management must be kept entirely outside the storage system’s trust boundary. This includes concerns about provider-level compromise, legal or regulatory constraints that prohibit storage providers from having any ability to decrypt data, or a deliberate architectural choice to avoid placing both data and key control within the same platform.

Advantages: Complete control over encryption keys. The storage provider never stores your keys or connects to your KMS. Keys are supplied per-request and discarded after use. This can be a hard requirement for certain classified, sovereign, or highly regulated environments, or in deployments where key management is intentionally owned by a separate team or system outside the storage platform.

Downsides: Operational complexity is very high. You must securely generate, store, distribute, and supply encryption keys with every request. Lose the key and the data is permanently bricked, with no recovery possible. Key rotation requires re-encrypting all data, often involving a full re-upload. Many tools and services, especially analytics and BI engines, do not support SSE-C at all.

Important to understand: You provide the encryption key with every request. The storage system uses it to encrypt or decrypt, then discards it. If you provide the wrong key or no key, the operation fails. This shifts complete responsibility for key management, availability, and disaster recovery onto your systems.

When to use: When you are using a third-party storage vendor and cannot or will not give them access to your KMS. This setup is uncommon and usually limited due to its heavy operational burden.

Client-Side Encryption

This is the zero-trust approach to encryption. Data is encrypted before it ever reaches the storage system and decrypted only after it is read back. The storage service never performs encryption or decryption and never sees plaintext data at any point.

As with customer-supplied keys above, all key management happens entirely outside the storage system. However, unlike customer-supplied keys, encryption and decryption must be performed by the applications and clients themselves, not by the storage service. The object store simply stores opaque, encrypted blobs.

Iceberg supports this model through table-level encryption. This model is still evolving. Query engines such as Spark are configured to connect to a KMS, and Iceberg defines which encryption keys are used at the table level. At the time of writing, Iceberg provides native support for AWS and GCP KMS, with other KMS implementations supported via custom integrations. When creating a table, encryption is enabled through table properties that reference a specific key in the KMS:

CREATE TABLE local.db.table (id BIGINT, data STRING)

USING iceberg

TBLPROPERTIES ('encryption.key-id' = '<master-key-id>');

Advantages: Maximum confidentiality by ensuring the storage provider never has access to plaintext data or encryption keys under any circumstances. This is necessary when the storage system itself must be excluded from the trust boundary.

Downsides: Operational complexity is extreme. You inherit all the overhead of running customer-supplied keys, plus every application and client must implement the same encryption and decryption algorithms, modes, padding, and key handling logic. Interoperability issues between different programming languages, SDKs, and cryptographic libraries are common.

Important to understand: You are effectively using object storage as a simple blob store. Features that rely on server-side processing, such as filtering or analytics, will not work. The burden of encryption, key management, and data recovery shifts entirely to the application layer.

When to use: Only when you explicitly cannot trust the storage system itself and cannot allow it to ever see plaintext data. This is rare and typically limited to niche regulatory, sovereign, or classified use cases.

Conclusion

Encrypting data at rest is critical for protecting sensitive information in data lakehouses. Apache Iceberg supports multiple encryption models, each with its own trade-offs between operational complexity, control, and trust assumptions. To summarize:

| Encryption Model | Control | Complexity | Use Case Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSE: Platform-Managed Keys | Low | Minimal | General-purpose workloads; meets most compliance needs; data is encrypted transparently by the object store |

| SSE: Customer-Specified Keys | Medium | Moderate | Multi-tenant workloads, regulatory requirements, auditability; allows key-level isolation; must manage KMS permissions and track keys |

| SSE: Customer-Supplied Keys | High | High | Strong separation of key and storage trust boundaries; storage provider never stores keys; operationally demanding |

| Client-Side Encryption | Maximum | Extreme | Zero-trust setups where storage must never see plaintext; all encryption/decryption and key management handled by applications and clients; interoperability challenges and high operational overhead |

When choosing a method, consider your security requirements, regulatory obligations, trust boundaries, and operational capabilities. For most cloud and on-prem Iceberg deployments, SSE-KMS (or the cloud-equivalent CMEK) strikes a practical balance between security, control, and manageability.

FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

How do enterprises actually run Apache Iceberg encryption at scale in production?

Most enterprises do not manage Iceberg encryption manually. In practice, platforms like IOMETE standardize encryption across object storage, Spark, and Iceberg catalogs so that encryption-at-rest is enforced consistently without per-job configuration drift.

Can Apache Iceberg encryption be enforced centrally instead of per Spark job?

Yes. While Iceberg itself supports multiple encryption models, IOMETE enforces encryption policies at the platform level, ensuring all Spark and Trino workloads write encrypted data by default, regardless of individual job settings.

How does IOMETE handle key rotation for Iceberg tables without re-encrypting petabytes of data?

IOMETE relies on envelope encryption via cloud or external KMS systems, allowing key rotation at the KEK level. This avoids full data rewrites while keeping Iceberg data compliant with enterprise key-rotation policies.

What encryption model does IOMETE recommend for regulated Iceberg lakehouses?

For most regulated workloads, IOMETE recommends SSE-KMS (customer-managed keys) because it balances auditability, access revocation, and operational safety without introducing the extreme complexity of client-side encryption.

How does IOMETE prevent accidental data loss when using customer-managed encryption keys?

IOMETE separates storage lifecycle operations from KMS ownership, ensuring encryption keys cannot be deleted or disabled without explicit safeguards. This reduces the risk of permanently bricking Iceberg tables due to key mismanagement.

Can multiple teams use different encryption keys within the same Iceberg lakehouse?

Yes. IOMETE supports key isolation at the catalog or workload level, allowing different teams, datasets, or tenants to use separate KMS keys while sharing the same underlying object storage.

Does Apache Iceberg encryption replace IAM and access control?

No. IOMETE treats encryption as a second security boundary, not a replacement for IAM. Object permissions, compute identity, and KMS access are enforced together to minimize blast radius in case of credential compromise.

How does IOMETE support encryption in hybrid or on-prem Iceberg deployments?

Unlike SaaS platforms, IOMETE runs fully self-hosted, allowing Iceberg encryption to integrate with enterprise HSMs, on-prem KMS solutions, or systems like HashiCorp Vault while preserving data sovereignty.

What happens if a Spark job tries to read Iceberg data without the correct encryption key?

In IOMETE-managed environments, the job fails immediately. Both object storage access and KMS permissions must succeed, preventing silent data exposure even if storage credentials are overly permissive.

Why don’t most enterprises use client-side encryption with Iceberg?

Because it breaks interoperability and operational simplicity. IOMETE supports client-side encryption only for extreme zero-trust cases, but most enterprises choose SSE-KMS to preserve performance, tooling compatibility, and recoverability.

How does IOMETE ensure encryption settings stay consistent across environments?

IOMETE applies environment-level policy enforcement, ensuring development, staging, and production Iceberg environments all use approved encryption modes without relying on engineers to configure each cluster correctly.

Is Iceberg encryption alone enough to meet HIPAA or GDPR requirements?

Encryption is required but not sufficient. IOMETE complements Iceberg encryption with audit logging, access separation, and infrastructure control, which are equally critical for regulated compliance frameworks.