Apache Iceberg ACID Transactions for Data Lakehouses

Data warehouses have been around for decades. They were designed to run analytics on structured data and provide the strong ACID guarantees enterprises traditionally associate with relational databases.

Over the last decade, data lakes emerged to handle the scale and variety of semi-structured and unstructured data that traditional data warehouses were not built to manage. While data lakes offered flexibility and scalability, they typically lacked the transactional guarantees enterprises depend on for analytics and governance.

Modern data lakehouse architectures aim to combine these two approaches: they provide strong ACID guarantees while also scaling to handle structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data in a single system.

At IOMETE, our data lakehouse platform has Apache Iceberg at its core, and we run it in production across customers with tens of thousands of concurrent jobs operating on multi-petabyte data lakes. Understanding the underlying concurrency model is essential to operating Iceberg reliably at enterprise scale.

In this four-part series, we explore how Iceberg enables transactional guarantees in a lakehouse environment. This first article focuses on a simplified, beginner-friendly introduction to the core concepts behind Iceberg’s consistency model.

How Apache Iceberg Provides ACID Transactions for Data Lakehouses?

Modern analytics systems still rely on the same transactional guarantees that have existed for decades, commonly referred to as ACID:

- Atomicity: changes are applied all-or-nothing

- Consistency: data remains valid after every operation

- Isolation: concurrent operations do not interfere with each other

- Durability: once committed, data is not lost

These guarantees are well understood in traditional databases and have historically been a core part of data warehouses, but not of data lakes. Data lakehouse architectures aim to unify both approaches, bringing strong transactional guarantees to systems built on scalable, open storage formats.

To introduce Iceberg’s transactionality, we'll use a simplified restaurant reservation system to illustrate the concepts; not because you'd build this with Iceberg, but because it makes the mechanics of Iceberg crystal clear.

Imagine a popular restaurant that only accepts reservations up to 30 days in advance. For each day, the restaurant keeps a single sheet of paper to track reservations. The goal is to avoid double bookings and ensure special requests are handled correctly. Now let's see how a traditional database would handle these reservations compared to Iceberg.

Traditional databases

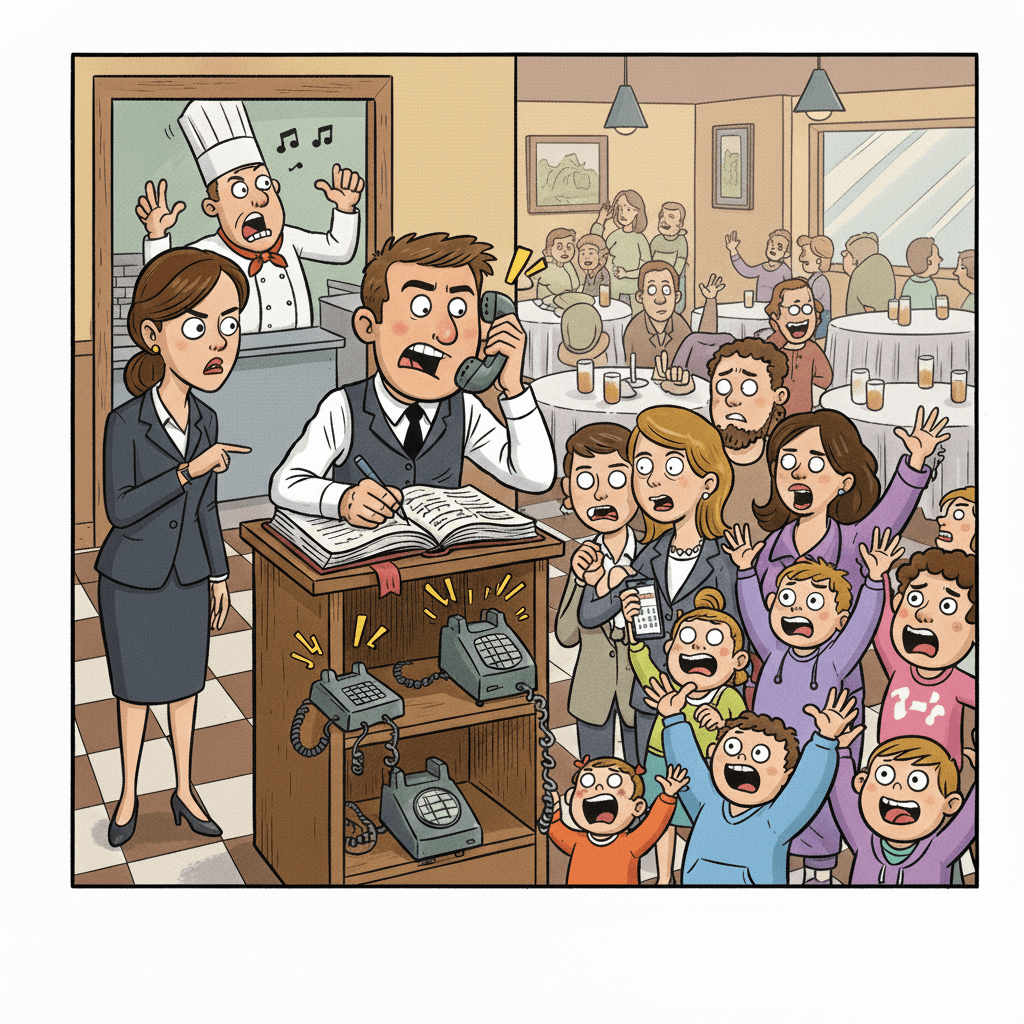

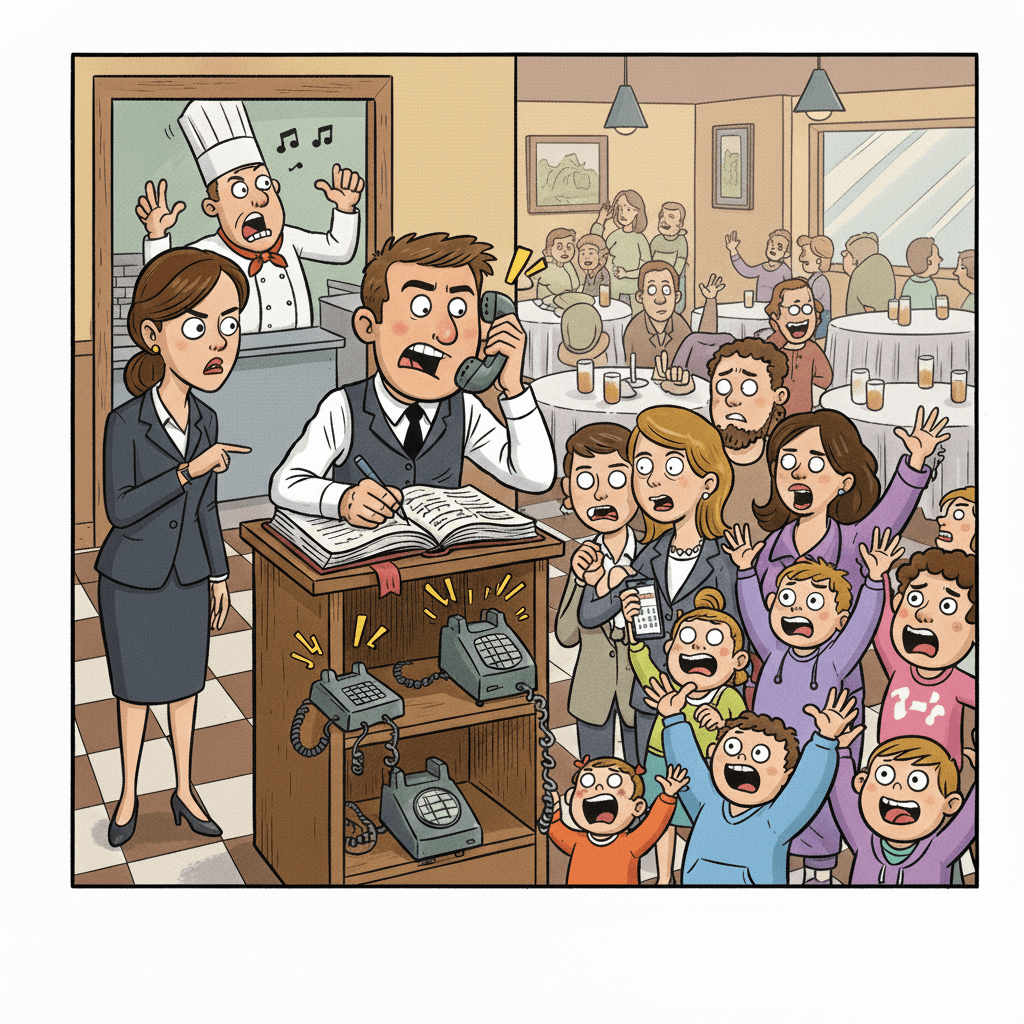

In a traditional relational database, all interactions go through a central server. Clients connect to the server to read or write data.

For our restaurant analogy, think of this as a single waiter maintaining the book of all reservations. Every customer has to go through this waiter to make or change a reservation. The waiter ensures that no double bookings happen and that every update is recorded correctly.

This approach has its limitations: when hundreds of customers try to check or update reservations simultaneously, the waiter can become a bottleneck. Long wait times and delays are inevitable since all actions must pass through a single person. This illustrates how traditional databases provide strong transactional guarantees, but can struggle to scale under heavy concurrent access. Similarly, when a concierge service places multiple reservations across multiple days for their exclusive clientele, the waiter becomes unavailable for other customers for quite a while.

Iceberg’s approach

Iceberg inverts the system above: rather than having a single waiter handle all the work, customers can make all updates to the reservation book by themselves.

Your first thought is probably that this won't end well if hundreds of people are writing at the same time. To prevent chaos, Iceberg follows a simple rule: once something is written, it is never modified. Every change creates new versions, and the key is limiting coordination to a single decision: which version becomes current.

In our restaurant, this works through sheets and a master list. Each reservation sheet (representing a day) can be copied and updated by any customer. When making a reservation, a customer first checks the master list to find the current version of the sheet for their desired day. They create a new copy with their changes and place it on the pile. Then they attempt to update the master list to point to their new sheet.

The update is accepted only if no one else has modified the master list in the meantime. If rejected, the customer retries: if their day's sheet hasn't been changed by anyone else, they simply resubmit the master list update. If someone else also updated that day's sheet, they create a fresh copy incorporating both changes and try again.

This setup ensures that everyone sees a consistent view of the reservations while allowing multiple customers to update independently. The only coordination required is agreement on which version the master list points to as "current."

How this enables massive scale

Allowing consumers and producers to independently access data files directly fundamentally changes the concurrency model. In a traditional database setup, all reads and writes go through a single service. This creates contention on latches, table- or row-level locks, write-ahead logs, and other shared coordination points.

Iceberg optimizes for read and write throughput by aligning its access model with modern object storage. Readers always operate on a stable snapshot, while writers never block each other when modifying data.

This design also cleanly separates “compute” from “storage”. In a traditional database system, a single server must be sized for peak load. With Iceberg, additional compute resources can be added during peak hours to handle writes. The storage scales independently from the instances handling the reads/writes.

As a trade-off, Iceberg accepts that writers may need to retry commits when contention occurs. Failed commits can leave behind stale files (aka orphan files), which are later cleaned up through maintenance operations. Additionally, every system interacting with an Iceberg table must implement Iceberg’s semantics. In practice, this is already handled by most major engines, including Spark, Trino, and Snowflake.

This setup allows Iceberg to scale horizontally: thousands of writers can work simultaneously, with the only coordination required being agreement on which snapshot is marked as "current”. That decision requires strong guarantees, and this is where the Iceberg Catalog comes into play.

How Iceberg provides ACID guarantees

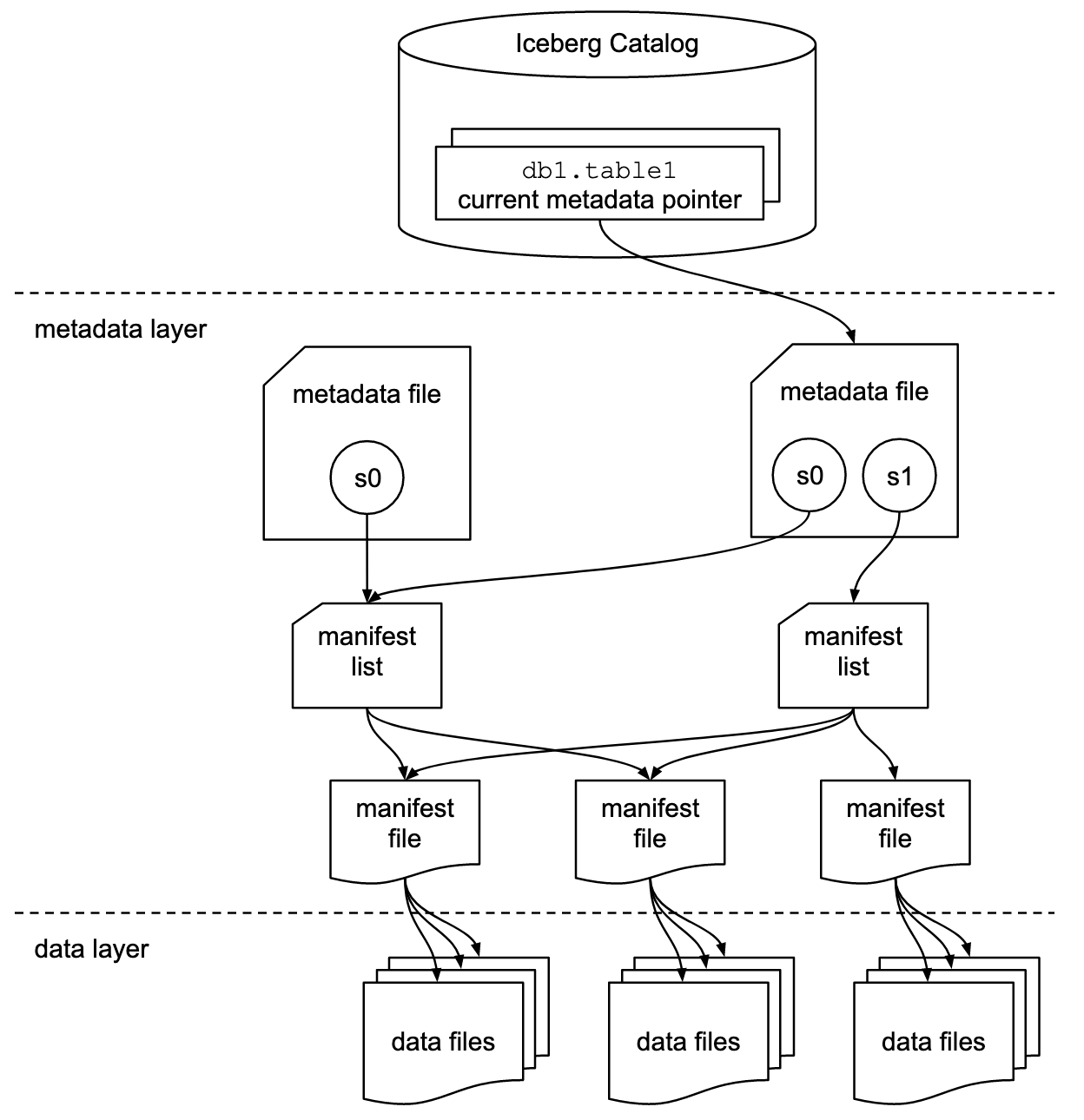

The Iceberg spec provides ACID guarantees through a careful organization of immutable files and a single coordination point that determines which snapshot is current: the Iceberg Catalog.

Iceberg organizes data using a small number of file types:

- Data files: the files that contain the actual data. In our example above, this would be the reservations for a particular day

- Manifest files: detailed inventories grouping data files by snapshot (e.g., which sheets were added/changed for a given version)

- Metadata file: the most important file, as it tracks which manifest lists belong to which snapshot, including which snapshot is marked as “current”

The Iceberg Catalog on top provides three functions:

- An overview of which databases, tables, and views exist

- Store the location of the “current” metadata file

- Provide a transactional way to update the current metadata file to a new one

For example, it is not uncommon to use a traditional database as the implementation of the Iceberg Catalog (known as a JdbcCatalog). At IOMETE, we provide a REST Catalog which currently uses PostgreSQL underneath to provide ACID guarantees when updating the pointer to the current metadata file.

The combination of write-once, immutable files and strong ACID guarantees when updating the pointer to the current metadata file is how Iceberg achieves ACID semantics.

Conclusion

Iceberg’s approach to transactions is deceptively simple: instead of coordinating reads and writes through a central service, it relies on immutable files and a minimal atomic operation updating the pointer to the current metadata file. All data and metadata files are written independently and never modified after the fact. Consistency is enforced not by locking files, but by atomically agreeing on which snapshot represents the current state of the table.

This design allows many writers to operate concurrently, while readers always see a consistent snapshot of the data. If two writers race, only one metadata update succeeds; the other retries based on the new state. Atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability emerge from this pattern without requiring all reads and writes to go through a central service.

In this article, we intentionally simplified the model using copy-on-write and avoided optimizations such as manifest pruning, incremental updates, and deletes. In the next article, we’ll make this concrete by walking through a hands-on example, inspecting the actual Iceberg files on disk, and seeing how these concepts play out in practice.

Frequently Asked Questions

Frequently Asked Questions

How do data lakehouses provide ACID transactions on object storage?

Data lakehouses provide ACID transactions by combining immutable data files with a single atomic metadata update that determines which snapshot is current. Instead of locking rows or tables, consistency is enforced by snapshot agreement.

This is the model used in production by platforms like IOMETE, where Apache Iceberg tables are accessed concurrently by analytics, ingestion, and AI workloads running at enterprise scale.

Why don’t traditional data lakes support ACID guarantees?

Traditional data lakes store files directly on object storage but lack a transactional coordination layer. Without commit semantics, concurrent writers can interfere with each other and readers cannot reliably identify a consistent state.

IOMETE addresses this limitation by operating data lakes through Apache Iceberg, adding a transactional layer that enables governed analytics on object storage.

How is concurrency handled in Apache Iceberg?

Apache Iceberg handles concurrency using optimistic commits. Writers never modify existing files; each write creates a new snapshot and attempts to atomically publish it. If another writer commits first, the operation retries.

This concurrency model is relied on by IOMETE in real deployments where large numbers of Spark jobs interact with the same tables simultaneously.

How does Apache Iceberg differ from traditional databases for concurrency?

What role does the Iceberg Catalog play in transactions?

The Iceberg Catalog is the single coordination point that tracks tables, identifies the current snapshot, and performs the atomic update that advances table state.

In IOMETE, the Iceberg Catalog is implemented to provide strong transactional guarantees when updating snapshot pointers under high concurrency.

How does Iceberg ensure readers always see consistent data?

Readers in Iceberg always operate on a fixed snapshot that never changes during query execution. Because snapshots are immutable, readers are fully isolated from concurrent writers.

This behavior is critical in IOMETE, where analytical queries must remain consistent even while ingestion and transformation jobs are running in parallel.

Why is immutable data important for scalable analytics?

Immutability eliminates in-place updates, locks, and shared write coordination, allowing systems to scale horizontally while preserving correctness.

IOMETE relies on this immutability model to support concurrent analytics, machine learning, and batch processing workloads on shared Iceberg tables.

What happens when two writers update the same Iceberg table?

How does Iceberg separate compute from storage?

Is Apache Iceberg suitable for enterprise-scale workloads?

Why this matters

Apache Iceberg shows that strong transactional guarantees can be achieved on open data lakes without centralized databases. By combining immutable files with atomic metadata updates, it enables scalable, reliable analytics.

This architecture underpins how IOMETE operates Iceberg in production today, and the next article will examine these mechanisms directly by inspecting real Iceberg metadata and data files on disk.